Way back in the olden days, when phones had cords, a camera was an expensive piece of equipment. A photographer outfitted for a shoot was weighed down with a giant bag full of lenses, film, flashbulbs, and nameless arcanery. Back in those days, my brother was a professional photographer. For some reason, that always suggests scantily-clad women in exotic beach locales, or on yachts, or at the very least a ski slope. But the reality is more mundane. All those catalogs and fliers that arrive in your mailbox are full of photographs, be they of coffee-makers, handsaws, or shoes. And each of those photographs, believe it or not, is artfully arranged in a studio, with appropriate props and professional lighting, in a layout designed to show off the object just so.

Sometimes those photographs are of food. I asked my brother once what the secret to a good food photo was. I was expecting an answer along the lines of "always include fresh herbs", or maybe a lecture about the golden ratio, but what I got was a look of surprise. The secret to beautiful food photos, he explained, is fake food.

Yep, that's right. Real food, it turns out, never looks as good as the fake stuff. A real roast has an annoying spot of oil in the wrong place. A real cake has frosting that is slightly irregular in a close-up photo, and couple of hours sitting under hot lights does not improve it. By the time the food stylist decides which shape of platter is really the most artful, real food has wilted beyond repair.

I remind myself of this from time to time as I'm blogging. All my food photos are the real thing, real food in my real kitchen, usually snapped just minutes before someone eats it. Sometimes I wish my photos were prettier, but I remind myself that that is how it goes. Real food is never going to be as photogenic as I wish it were.

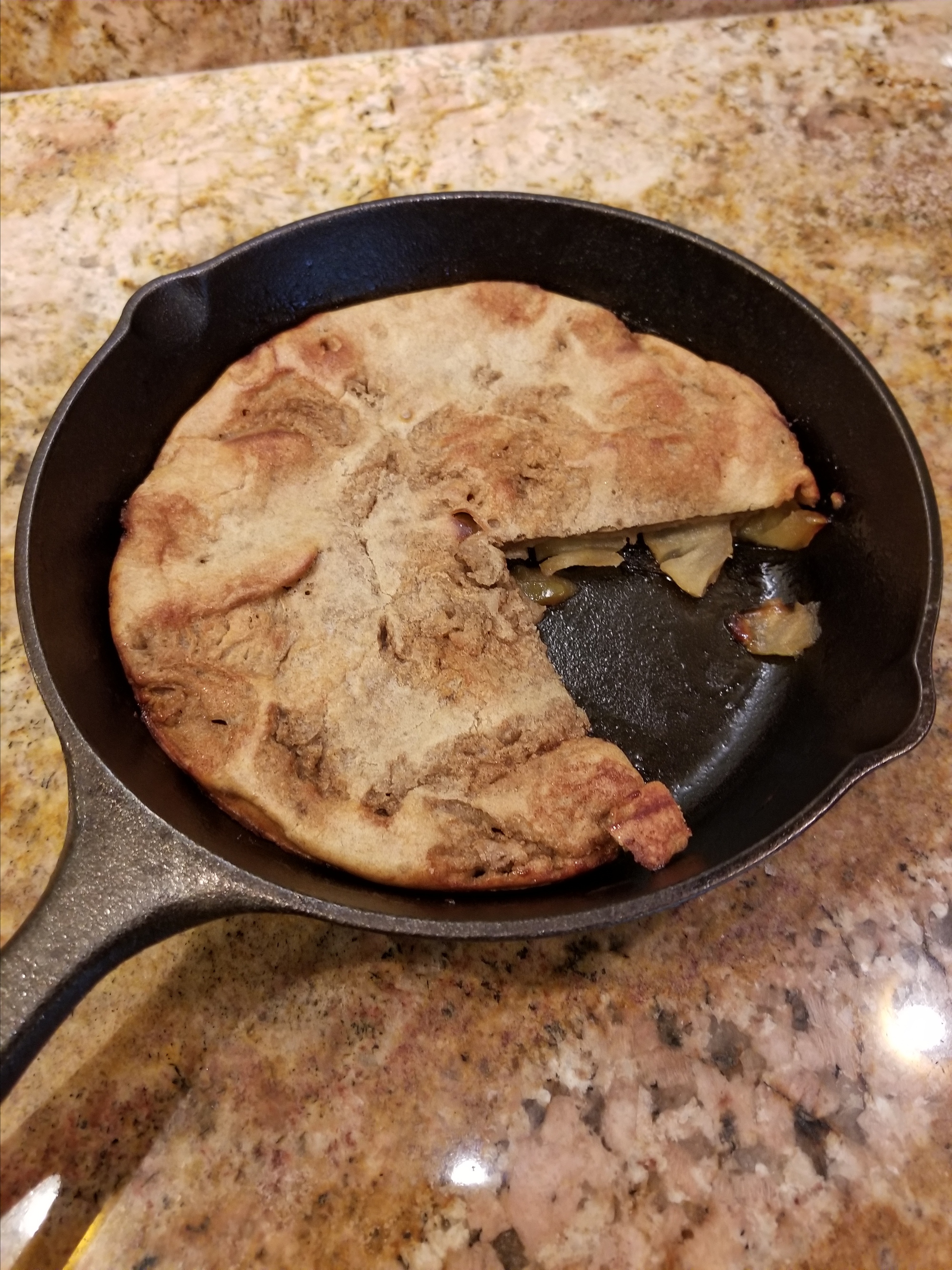

That doesn't stop me from trying. I made three flourless chocolate cakes one weekend, trying to achieve something that looked more appetizing than a hockey puck. But there are limits. When I made this apple pancake, I knew I had met my match. It's not ugly, exactly. In the baked flesh, I would say it has a certain rustic, homespun appeal. But in photographs, it just sits there. What can I say? Trust me, it's delicious.

This baked pancake is first cousin to a clafoutis, just as delicious and almost as easy. And, it has apples! I bet you didn't think I could sneak apples into another dish, but you were wrong. This pancake has not only apples, but also maple syrup. It's a marvelous weekend treat. In the spirit of truthfulness, I have to disclose that it is slightly more work than a clafoutis. You have to cook the apples before you make the pancake, and that takes a good 15 minutes. Somewhere in this world there are morning people who spring out of bed with a song on their lips. Those people probably get up 15 minutes early when they are making a complicated breakfast. I am not those people. I do all the pre-work the night before.

This recipe specifies Granny Smith apples, which I think are great in baked goods. So I named the recipe after Maria Ann Smith, who is credited with cultivating the first Granny Smith apple, the result of accidental hybridization. I don't know how photogenic she was, but she definitely knew a good thing when she tasted it.

Notes

This is a gluten-free pancake. If you do not want a gluten-free pancake, you can substitute all-purpose flour, bread flour, or whole wheat pasty flour instead. They are all delicious.

It goes without saying, but I will say it anyway: you should use real maple syrup in this recipe. Maple-flavored syrup won't do.

The pancake will be best if you take the trouble to slice the apples uniformly, and not to thin. This will allow them to cook through without getting mushy. And despite my loyalty to Granny Smith, I'm sure many other varieties of apple would work here as well.

Inspiration

This recipe is adapted from "Baked Apple Pancake" in Prairie. In addition to half-sizing it and making it gluten-free, I also had to do a bit of translation. The original recipe seemed to call for a good many apples. I've noticed other recipes in this book that seemed to require way too many apples: either Granny Smith apples used to be much smaller, or the size supplied to restaurants is smaller than the size they sell at my grocery store. I would describe the apple I used as "medium-large" and it weighed about a half pound. Given how varied apples are in size, I think weight is a lot more exact than count.

The original recipe also specified "a medium-sized, oven-proof saute pan". And then at the end it says it makes "1 large or 2 small pancakes". None of that seemed to add up to me, so I looked at a lot of different recipes online to decide what size of saute pan might be appropriate for the original recipe, and what size to try for my smaller version.

One part of the original recipe totally made sense, though. That was the note that says "This also makes a great dessert, served hot with whipped cream or ice cream." Yum.

Comments powered by Talkyard.